There are some bird species that have, as their primary Wikipedia photos, images not of living birds but mounted taxidermic specimens. These include the imperial woodpecker, endemic to Mexico, not seen since 1956; the Carolina parakeet, the only parrot indigenous to the eastern, midwest, and plains states of the U.S. until the last individual died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918; and the great auk, a storied bird who, as their numbers plummeted, became increasingly valuable for their skins and eggs, which museums and private merchants started paying big bucks for.

Upon request of such a merchant, in 1844 on the island of Eldey, off the coast of Iceland, the last two great auks in the world were killed. “[I] caught it close to the edge – a precipice many fathoms deep,” Sigurður Ísleifsson, one of the hired men, recounted in 1861. “Its wings lay close to the sides – not hanging out. I took him by the neck and he flapped his wings. He made no cry. I strangled him.”

Every time I read this account, I get stuck on the pronoun shift: the word “it,” which Ísleifsson first uses to describe the male auk, becoming the word “he,” which Ísleifsson turns to by the end. At first, Ísleifsson seems to see the auk as a lifeless thing, already a specimen, an object, cash in hand. But, as he takes hold of the bird’s neck, suddenly “it” is a “he” Ísleifsson is grappling with, overpowering, then murdering. The pride and pleasure he takes in his actions is enacted through the language he’s using to describe them—the cruelty is at the surface. Cruelty, too, that the pair of auks were nesting; as Jón Brandsson and Ísleifsson killed the adults, a third member of the party, Ketill Ketilsson, crushed the sole egg under his boot. The species was already eliminated by this point, so this act doesn’t make a huge ecological impact, but I get stuck at that part, too.

Cruelty is not the reason more than half of U.S. bird populations are in decline. I remember when I first moved to New York, I was shopping for winter coats somewhere in midtown, and suddenly, among throngs of shoppers on the sidewalk above a rumbling underground subway station, I became overwhelmed with the feeling that I was causing destruction everywhere I stepped, that my very existence was destructive. In a panic I called my friend Leah, who reminded me that I had a right to be on earth simply because I was here already. Most people don’t feel personally responsible for that 48% because, well, we’re not, not really, and we wouldn’t choose it if given the option. Not many of us want the birds to disappear. Generally speaking, we like birds. We don’t like to hear that story about the great auk. And no one, not one person on earth, made the decision to show up here. We just did, and we’ve got to live, too.

But what is cruel, in its many mundane shades, is that there are a ton of massively huge profit-making machines that benefit from the conditions leading to the extinction of wild animals all over the world, and very, very few that would benefit from their survival. Given that the United States is by far the largest economy in the world, our system–Amazon, Exxon-Mobil, Citizens United–goes far beyond the choices any individual person can make. Yet these systems are human inventions, American ones, and whether they became cruel by some unfortunate circumstance or were designed around cruelty, they are our lineage.

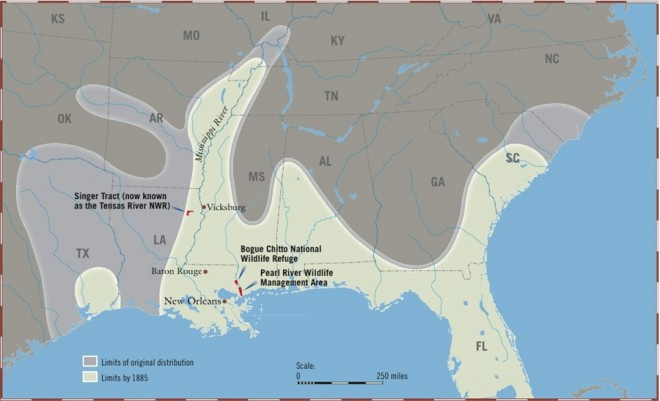

One Wikipedia page, a page I visit often, is headed by a grainy black and white photograph of two huge birds, one inside a tree cavity, the other scaling the trunk beside it. Ivory-billed woodpeckers ate beetle larvae and persimmons, mated for life, and measured an astonishing 20 inches long with a 30 inch wingspan–2 and ½ feet tip to tip, or roughly the height of a toddler. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the birds’ primary habitat, the bottomland hardwood and temperate coniferous forests of the southern U.S., was heavily logged and the woodpeckers extensively hunted until many ornithologists considered the ivory-billed woodpecker functionally extinct by 1920. However, in the early 1930s, Cornell professors Arthur Allen and Peter Paul Kellogg, Ph.D. student James Tanner, and avian artist George Miksch Sutton organized an expedition to northeastern Louisiana, where an ivory-billed woodpecker had been shot and killed. There, on a piece of land known as the Singer Tract, the team located a population of 6-8 woodpeckers.

The Singer Tract was named for the Singer Sewing Company, which then owned it. The logging rights were held by the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. After the team took photos and video footage of the birds, they reported back to the National Audubon Society, which attempted to buy logging rights to the tract. The Singer Sewing Company rejected their offer. In 1944, when logging of the tract was nearly complete, the Audubon Society president sent 23 year-old artist Don Eckelberry to the area. He found and sketched a lone female. It is the last universally accepted sighting of the bird.

In 2021, when Amy Trahan, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, completed the species assessment, she checked a line next to the words “delist based on extinction.”

“It was probably one of the the hardest things I’ve ever done in my career,” she told the New York Times this year.

In 1980, part of the Singer Tract was turned into a park, forty years after several governors of southeastern states signed a joint petition urging the company to do just that, and forty years too late for the ivory-billed woodpecker, but spotlessly aligned to the moment that the land stopped making money: 1980 is also the year that the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company went out of business. The Singer Sewing Company still exists, though they’ve outsourced much of their operations to China, Vietnam, and Taiwan. I’m suddenly remembering a marketing class I took in 2009, as an undergrad, when the professor explained to us the life cycle of a brand. “Eventually, they will all disappear,” she said, as we watched the Coca-Cola logo rise, then fall, along an X axis. I remember staring at the red letters dissolving on the screen in front of me–it seemed inconceivable then to imagine a world without Coca-Cola. Fourteen years and as many major societal changes later, it isn’t any less strange to think about how much time, effort, labor, and money go into the creation of things we find so incredibly important when we’re alive, even though none of them will go with us to our graves, even though all of them will find their own ends, too.

Maybe it’s one of the intentions of this essay: preserving, if only in writing, what is no longer here that should be here still. But it’s really the film I want you to see.

The pair of ivory-billed woodpeckers has no idea they are among the last of their kind. They are, it seems, taking care of hatchlings inside the tree cavity. They’re trading places so one can keep watch while the other goes out for food. They aren’t curious about the people filming them, what they’re doing, why they’re there. All around them, employees of the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company are felling trees, making money for the Singer Sewing Company–both companies hurtling, at different speeds, towards the inevitable brand death that they will experience–and through the woods, the woodpeckers keep calling to each other, just like they’ve done for as long as they’ve been on Earth. But you can’t hear anything: the footage is silent.

It’s nine years from this moment that Eckelberry will find and sketch the last remaining bird. This pair–and their offspring–are almost certainly gone by, if not shortly after, the time he leaves the tract for home.

This year, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced it was extending its review period to determine the status of the ivory-billed woodpecker. Reports of sightings of the bird have been shared (and mostly debunked) on the internet for years, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has yet to change its status, still listing the bird as “critically endangered.” But if there are any ivory-billed woodpeckers out there, it’s hard to imagine how they will escape simply becoming one of the almost half of U.S. bird species headed towards extinction. It’s not because of individual cruelty, per se; this would be a different essay if it was. It’s about the machine of profit, about how so many of us never question its functions. If one person, or maybe a few, at the Singer Sewing Company had stepped in in the 30s, it’s possible the ivory-billed woodpecker would still exist today. Instead, we have annihilation, and no way to reverse what we’ve done.

“It is, or was, the largest woodpecker in the United States,” the bird’s Wikipedia page says. Again, I get hung up on grammar–the shift from present to past tense, or at least, the question of it. It is, or it was. There’s a choice implied, one we haven’t taken yet. At the same time, that black-and-white shot, a still from the footage that the Cornell team took in the 30s, makes the entire web page into an elegy. It’s a feeling I have sometimes looking at trees–that I’m somehow mourning something at the exact same time that I’m desperately trying to find new ways to make it live.

One of the worst things that American mainstream media does to the environmental movement is sensationalize climate news. Apocalyptic headlines sell subscriptions, and they also make all of us feel like helpless bystanders, gloom factories doomed to keep reading, enticed by the idea that there might be some kind of pot of gold at the end of the article that will make us feel better. It’s human nature to do this–feel bad, then want to feel better–and a lot of us fall for the trick. If I’m being honest, I fall for it pretty much every day.

Here, I’m trying to find some middle ground, some place where all of us can meet and discover something that doesn’t exhaust us. I have very little idea how to do this, but what seems worse is letting this self-motivated, self-aggrandizing system bring us somewhere in our minds, or our experiences on Earth, that we don’t actually want to be. It seems to require both accepting responsibility as individuals and as a collective, which requires seeing the power that collectivity has, which requires imagination. Capitalism encourages us to see ourselves as we’ve always been, to block from possibility being any other way. Nature teaches us differently.

On that note, I leave you with more footage, this time of a bird called the black-naped pheasant-pigeon, last spotted by researchers in 1882 and not since, until now. Captured by a camera placed on a 3,200 foot ridge on an island off the coast of Papau New Guinea, this footage shows a bird that looks a lot like the New York pigeon with more color and a very fancy tail: an animal previously assumed to be a fluke, a mystery, or gone, and yet an animal that is none of those, though it is, clearly, one of a kind, or at least beyond the reach of our understanding—which we have to admit, is more limited than we probably know.

See you next month.

“I’m somehow mourning something at the exact same time that I’m desperately trying to find new ways to make it live.” I’ve had this feeling but never knew there were words for it. Thank you for your eloquence.