I wasn’t planning on including an essay about Florida in this series, considering its setting, if there is a setting, is New York. But in December, I went back for the first time in four years–I moved away almost a decade ago–and realized how much of my home is threaded through the ethos of these essays. Growing up in the Sunshine State, a state with no income tax, a state that is expected to double its population over the next 50 years, a state known for natural beauty which is in turn particularly susceptible to profiteering, a state that always seems to harbor the far right, other people’s vacation state, the state where other people go to die, is, as it turns out, exactly why I write this series at all.

Truthfully, though, I’m a little embarrassed about it. The last few years of my life in Florida were tumultuous, and when my family moved away, I also bolted, emotionally speaking. I would joke about being from Florida, reassert to others the many ways I never felt like a Floridian, or make disparaging comments about cultural stereotypes: Salt Life, sunburnt white men holding four foot long fish in Tinder photos, eating at the Panera, gun shows, sweatshirts in July, hanging chads, etc. Every turn of phrase was a defense; I did not belong, never belonged, would never belong, so I left.

But I was never a birder in Florida. While my mom has always been an avid bird lover, it took me years and a global pandemic to catch on myself, and by then I was already living in New York, my parents were already living in Georgia, I wasn’t talking to my ex or most of my Florida friends anymore, and the place was, in most ways, dead to me, and me to it. I remember birds growing up–once, an egret stalked me on my way home from the bus stop, all the way to my front door, which they stood conspicuously on the other side of staring at me through the paned glass after I let myself into the house–but birds were not of me, not part of my understanding of where I came from.

At least on the outside, it seems, most people in Florida don’t understand themselves in relation to birds, or wildlife in general, or nature at all. It’s not like this is unusual–you could say the same thing about many New Yorkers–but it’s ironic because Florida is advertised as where to go to get away from it all; when people talk about why they move there, it’s often for the weather or the beaches or whatever. And people are moving there. I remember a few years in early high school, 2005-ish, where the neighborhood outdoor cats kept disappearing; eventually, it was discovered that there were coyotes moving through our yards at night, displaced by the housing developments going up east of I-75. Then the coyotes weren’t there anymore. That was twenty-something years ago now; in 2020, my hometown, Sarasota, was number two in the country for population growth to population loss: an increase of 78% compared to a loss of 22%, just behind Wilmington, North Carolina. Instead of trees lining the interstate, there are walls now, sound barriers for brand new neighborhoods. Where old style Florida homes used to stand along Fruitville Road, there are multi-story condominiums. In more than one shop, I saw postcards of buildings that have been torn down, turning the entire experience of visiting into a kind of aspiration, a nostalgic gesture towards a place that doesn’t exist anymore.

To accommodate the growing population, my part of the Gulf Coast has changed. The Florida I remember was full of huge swaths of empty land, agricultural or wild. My mom can tell you about seeing scissor-tailed flycatchers hovering over the fields that used to run alongside 681, their long tails floating and transparent in the early morning sun, and how gradually they started to disappear the older my sister and I got. I don’t remember ever seeing one. When I drove 681 in December, many of the fields themselves were gone, replaced by sprawling new construction.

If population trends continue as predicted, in order to accommodate 18 million new residents by 2060, 7 million acres of land–the equivalent of the state of Vermont–will be converted to housing and urban use in Florida. Thoughtlessly done, this means an endless expanse of strip malls and parking lots and lawns, a real life concretization of the angsty, adolescent way I saw my home state when I was younger. In many ways, my younger self saw it right; in December, driving around, I noticed that every new neighborhood had, in every way, replaced open land or trees–wild land entirely razed to the ground, every tree, bush, and plant taken down. Without exception, the process seemed to start with complete annihilation. Then, what had cropped up in its place: concrete. Steel. Stucco. Decorative plants, an aesthetic landscaping that people often confuse with “nature.” (More on this in a future essay.)

This is the part where I start to get anxious. After all, hating on your home state is such a played out cliche at this point that it makes me sort of rude to hold your attention on this right now. Hating on your home state when you haven’t lived there in almost a decade–and! when you decided to move away to New York City, of all places!–is embarrassing. I did it; I knew I wanted to try living in the northeast; I was, if I’m being honest, entranced with myself for having the idea and the gusto (and the resources) to do so. As we were breaking up over this, my ex particularly seemed to enjoy reminding me of this sense of superiority, and they were right: I felt too important, too seen, too big already; I wanted more, and I wanted anonymity, not least because I needed it to separate myself from my past and start over.

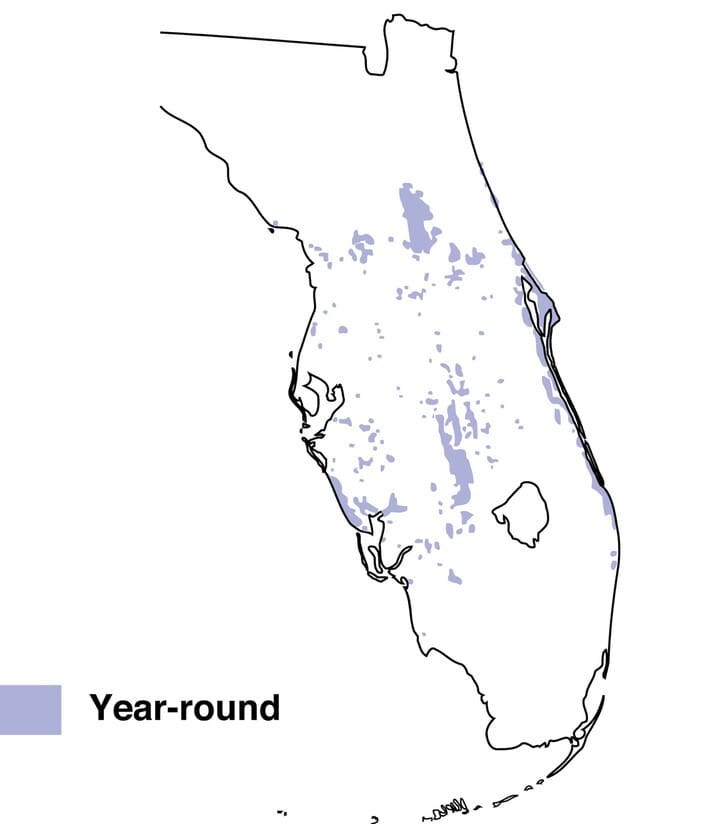

And there’s overlap–obviously, there’s overlap–between my desire and the desire of others to uproot wherever they’re from and move elsewhere–maybe, possibly, Florida. So, I don’t feel like I have the right to write this way, or about Florida at all, even though I was born and lived and sometimes felt like wanting to die there for 24 years. My own narrative is traumatized, and my experience feels fractured. In being unable to piece it together, I lose my hold on it. There’s no center, like the distribution map of the scrub jay, which looks like a Florida-shaped paper towel spotted with tiny, itty bitty drops of purple, where the endangered birds live, breed, and die.

I also loved much of my life as a child. My parents did appreciate the natural beauty of Florida, and I remember tent camping, building forts in big stands of trees, playing hide and seek by the creek, bare feet, bug bites, the works. In a recent text conversation with my friends from high school, one said that Florida is where he met his favorite people in the world, and I’m reminded that deep relationships, the deepest ones, are often forged in some kind of hostile environment, and childhood is nothing if not hostile. Even if it is joyful, as mine was, being a child is edged with a sober, unrelenting taking-in that we get much better at avoiding, for better or for worse, the older we get. Even as I’m crying by the side of US 41 about the trees, there’s a part of me sitting beside, looking sidelong, because of course things are going to change–it’s been almost a decade, a decade in which a lot of shit happened, much of which has resulted in people deciding it’s a good idea to move to Florida. What did I expect? Even growing up there, even living there again as a young adult, back in my parents’ house after college, I knew this was what Florida was. It couldn’t ever not have been.

At some point as we drove down Memory Lane, I realized that the premise of the trip was fucked from the start. While I thought it would feel good to see some old friends and felt like it would be meaningful to show H around my place of birth (and both of these were true), the pull was darker–I wanted to somehow fix the way I left the state the first time. I wanted to either deeply regret leaving it or I wanted to leave it again, this time for good. Instead, what I realized was that I never really left, and I’ll never really be back, either. In everything I do, I carry Florida with me: the sense of promise, the edge-of-the-world feeling you get as a teenager driving all by yourself alone on empty interstates, the transience, the restlessness, the wanting more. I’m also changed. It’s also changed. The Florida scrub jay, for example, numbers somewhere between 2,500 and 10,000 individuals in the wild; in order to thrive, the bird requires a scrubby, sandy habitat that only exists in Florida, where the bird is endemic, found nowhere else. H and I went looking for one at Oscar Scherer State Park, where I used to hang out a lot as a kid–it has the perfect habitat for the Florida scrub jay–but I later found out one hasn’t been spotted there since 2018.

There are, at this point, more people than ever on Earth, and tomorrow there will be more, so preserving some idyllic version of the past isn’t an option for Florida (or myself.) What is? I think about my compulsion to write this essay in the first place–to try to revisit the idea of home through the lens I take in this series–and what I’m ending up with so far: something a little incomplete, an essay that feels like the roadways that carry traffic over Tampa Bay–roads that at first skirt along the edges of salt marshes and mangrove stands before unrolling out into the bay a few feet above the water’s surface, curving and glancing across the top of each thin spit of land between St. Pete and Bradenton. I loved driving those roads. Despite hating car culture, despite hating everything that tourists like, no feeling I’ve ever had compares to driving that stretch of I-275, and I love it as much at 32 as I did when I was 16 and ditched school with my best friend to do it.

(I wish I had taken some footage of this drive myself, but I appreciate the internet for having this available.)

My emotional body, the one that heats up whenever Florida is even mentioned, was full of heat for the week I was there. Yet those roads still healed. And in the ecological body that is Tampa Bay, or the Gulf Coast, or Florida, or the whole country, maintaining healthy connections can help heal what human development has done and continues to do. Migrating birds need flight routes with reliable shelter and native food and water sources; deer and raccoons and foxes and Florida panthers need safe passage across interstates; the scrub jay needs more than tiny islands of habitat slowly being eaten away by asphalt and lawns. We need access to the disparate parts of ourselves in order to understand the whole, to understand how to function. Picture the lattice of an apple pie. Picture a collection of tree houses, connected by swinging rope bridges, the kind you might dream up as a kid.

In April 2021, the Florida House and Senate passed the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act, $400 million in funds dedicated to restoring and maintaining a network of interconnected parks, forests, rivers, streams, and working land like ranches and timberland that provide habitat for wildlife. But changes to the state budget later that year jeopardized the act’s potential effectiveness. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission runs a landowner assistance program that helps inform and support private landowners who are interested in improving habitat conditions on their property. But it’s voluntary, cooperative, and not something that is required of any individual landowners, let alone those companies often responsible for scorched earth methods of housing development. The attention and care required to oversee these kinds of programs is imperiled by the political fabric of Florida, a highly segregated, gerrymandered, voter-oppressed entity currently held hostage by Ron DeSantis’ slogan “Keep Florida Free.” (I don’t really get it. It’s not freedom to be forced, as an individual, to take on deeply entrenched power brokers like developers, governors, even homeowners’ associations in order to actually connect to the place you’ve been sold on. But that’s the case everywhere–in New York, in Florida, in every state in between.)

Despite the fact that it’s not how I’ve done it, it does seem easier to draw a clean boundary, to make a break for it, or whatever language we tend to use when we talk about leaving home. On some level, it was what I wanted to do. But many things—friendship, love, fear, need, a desire to replicate, a desire to restore—have led me time and time again back to Florida. This time, the wait at Owen’s Fish Camp was 3 and 1/2 to 4 hours, there are roundabouts where there used to be stop signs, and both my memory and the landscape were fragmented—nature and personal history intertwined.

One bird I looked for when I was in Florida was the roseate spoonbill, a bright pink bird with a distinctive bill. I didn’t spot one, but I did find out that roseate spoonbills are a conservation success story: the species was virtually eliminated across the United States because of the destruction of wader colonies by people hunting the bird for its feathers, but they began to repopulate coastal Florida and Texas in the 20th century, and their population has rebounded, though they are still considered vulnerable. Interestingly, climate projection models run by the Audubon Society show the roseate spoonbill gaining range in the coming years rather than losing it. I am reminded, once again, about the unpredictability of the future, a feeling I flew away on ten years ago, before I knew how to miss what I would soon, inevitably, miss.

It’s here that I want to end this particular submission to the Mortal Lives filing cabinet–on somewhat of an unfinished note, on a bird I didn’t actually find, and on the sense that I flew back north with: if your past means more to you the older you get, it’s best if you can let a little bit of it go too. If you don’t, you’re going to keep trying to write the same thing over and over; you’ll keep going back to your own doorstep, looking for something that is no longer there.

This expressive writing is masterful in the journey on which it takes the reader. The passenger goes along ensconced in the story, then finds themselves turning a corner, onward to another story. With each corner turned the story deepens and expands, be it beautiful or dire. You’re dropped off at the final corner, and watch the writer and the car continue on her journey into the future.